I wrote

yesterday about a Monkeycage blog entry in the

Washington Post about new empirical research regarding rural resentment and its impact on politics I'd noticed that shortly after the article was posted to the

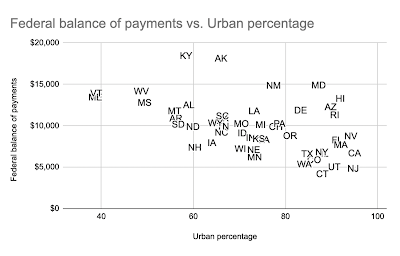

Washington Post website, Paul Krugman tweeted a three-part response in which he wrote, "what's depressing about this is that in reality rural America is heavily subsidized by urban America."

Then in part 2 of his little tweet storm Krugman continued, "You can see this by looking at states' federal balance of payments--what they receive versus what they pay. Huge inflows to the most rural states." Then in Part 3: "But of course if you point that out rural voters will just see that as another example of elite disdain. It's really a no-win situation."

Then on Friday, just a day after the Monkeycage item appeared, Krugman wrote a column titled "

Wonking Out: Facts, Feelings and Rural Politics." In it, he expands on his dispute with the "feelings" among rural folks that they don't get their fair share from the government. Here's an excerpt:

Political scientists have found that rural Americans believe that they aren’t receiving their fair share of resources, that they are neglected by politicians and that they don’t receive enough respect. So it seems worth noting that the first two beliefs are demonstrably false — although I’m sure that anyone pointing this out will be denounced as another sneering member of the urban elite.

The truth is that rural America is heavily subsidized by urban America. You can see this by looking at states’ federal balance of payments — the difference between federal spending in a state and the amount a state pays in federal taxes. Here’s a plot of those balances, on a per-capita basis, in 2020 versus urbanization in the 2010 census (the most recent data available)

Krugman cites the Census and Rockefeller Institute for these data.

The first problem I see with Krugman's analysis is that he uses the scale of the state rather than, say, the county. This is ham-handed and lacking in nuance (see more below from Hildreth and Pippa). That is, it fails to consider what is happening within states--what percentage of federal dollars flow to, for example, metro counties versus nonmetro ones. It reminds me of when elite colleges brag about their geographic diversity, but it turns out the students they admit from Montana are from Billings and Bozeman, or those they admit from Utah are from Salt Lake City.

Krugman "points out that 'rural America is heavily subsidized by urban America' and 'Donald Trump sent $46 billion in aid to farmers.' Does he really think all rural people are farmers? WAY more rural people work in the care economy and in manufacturing than in ag."

"Rural and farmer are two very different things. On-farm employment accounts for only 2.8 million people. In contrast, there are 60.8 million people in the rural U.S. ... Stereotypes perpetuated by [Krugman] suggesting that 'ag subsidies are the same as 'rural economic opportunity' create even more resentment in rural America. With the corporate consolidation, ag subsidies go to fewer and fewer people"

"To really understand rural rage, @paukrugman should look at manufacturing and health care jobs in rural America. Those industries have a much bigger impact on rural jobs than farming."

"When a rural hospital closes, i tis devastating for jobs in a rural community of 2,000 rural U.S. hospitals, 150 have closed since 2005, and more than 300 are at risk."

"NAFTA was devastating for rural manufacturing jobs."

Krugman "forgets that Barack Obama had a very strong performance in the rural Midwest. And Obama said he would 'renegotiate' NAFTA during his primary against @HillaryClinton. Obama won the Iowa caucus and later abandoned his anti-NAFTA stance"

"The good news is that a new generation of Dems like @RepDerekKilmer, @AngieCraigMN, @RepCindyAxne, @TinaSmithMN, @repohalleran, @repjoshharder, @gillibrandny and @SenMarkKelly understand the real issues in rural America and are focused on solutions."

"The reasons why 'rural perceptions are so much at odds with reality' as [Krugman] writes is because he and the [New York Times] haven't written anything about all of these things Democrats are doing to delivery for rural people. If the media won't cover it, how do voters know about it."

"They lack capacity because of decades of disinvestment by states and feds ini rural local govts, and b/c of their own fiscal policies that have historically depended on industries that have declined or left--and it's been tough to adapt."

"Also a big problem of fed investment in community & econ devp is decided by states and thus v. hard to follow/analyze. So all of that is missing from [Krugman's] analysis.

"Talk to any local rural leader, and they'll tell you how much of that they get... and it ain't much."

Krugman "himself acknowledges that the balance of payments basically reflects greater social safety net spending.

"That's exactly it! Fed $$ are going to rural folks to barely keep their heads above water, rather than offering investment to help their communities succeed."

"Thanks to [Krugman] for engaging with our piece in @monkeycageblog. A couple of quick responses, tho:

1. His balance of payments analysis focuses on the urbanish states vs. ruralish ones. But there are urban areas in rural states & vice versa. It depends on how you slice it, but ..."

"there's data showing that, within states (e.g., Florida, Wisconsin, etc), per capita spending to rural areas is lower than in cities.

2. Relatedly, given that rural areas both fuel and feed urban America, rural states ought to [be] heavily subsidized and maybe aren't subsidized enough.

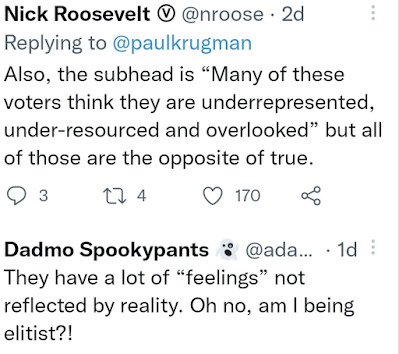

3. Krugman claims that rural people bash cities as being crime ridden hell holes but he can't recall instances of urban disdain toward rural areas. This is an incredible claim and evidence that Krugman doesn't read replies and QTs of his own tweets lol. For example... "

"Hateful people try to justify their hate by telling themselves that the object of their hate hates them."

"Why aren't rural Americans hustling for work in the cities or studying their asses off to get into top schools, also in cities? Why don't they learn from immigrants and hustle like them instead of whining?"

"Also, the subhead is 'Many of these voters think they are underrepresented, under-resourced and overlooked' but all of those are the opposite of true.

"They have a lot of 'feelings' not reflected by reality. Oh no, am I being elitist?"

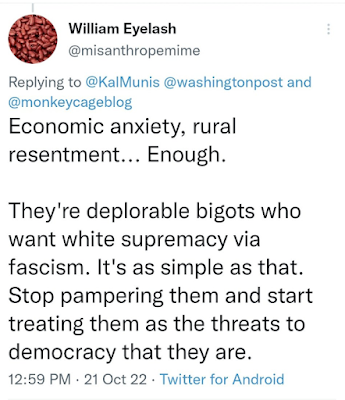

"Economic anxiety, rural resentment... Enough. They're deplorable bigots who want white supremacy via fascism. it's a simple as that. Stop pampering them and start treating them as the threats to democracy that they are."

The Daily Yonder published analysis in 2011 and 2014 about what rural folks get from the federal government government and whether they are "subsidized" by urban folks. Those pieces by Bill Bishop are

here and

here.