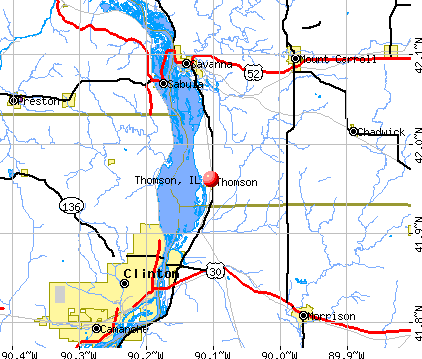

Today's New York Times ran a story about the small rural town of Thomson, Illinois faced with the prospect of housing Guantanamo Bay inmates in its local prison. Thomson is located in Carroll County, right on the Mississippi River.

Much like the other prison town stories found on this blog (see here and here), there is a combination of fear and desperation amongst the residents of the city. On the one hand, they're uncomfortable with the idea of having terrorist in their midst:

“It’s the terrorist-type thing that gets me,” said Donald L. Pauley, 64, who said he felt queasy at the notion of such prisoners being kept here, 150 miles west of Chicago, a place where everyone acknowledges that signs describing the population as 600 are overestimates by now.

Yet, on the other hand, Thomson residents deeply desire a boost to their local economy:

But, in one example of the split that is playing out all over this village, even within houses, Mr. Pauley’s wife, Merrie Jo, said she was firmly behind the idea of turning over the Thomson Correctional Facility, a barely used state prison, to federal authorities, in part for those from Guantánamo.

“We need the jobs,” Ms. Pauley, who was the village president here for 27 years, said as she and Mr. Pauley dined at the Sunrise Restaurant, one of the few restaurants still open in an area where unemployment was 10.5 percent in September. “This place has been changing, and we’ve been going in the wrong direction.”

The article also brings up issues of anonymity, rural brain drain and population loss - all things we've spent a lot of time discussing in class this semester.

The notion that a terrorism suspect could slip away into Thomson without notice was unimaginable to Ms. Pauley, who added, “If a stranger comes around here, everyone knows within 20 minutes, believe me.”

Leaders in Illinois have said moving the prisoners here could bring as many as 3,200 jobs to the area. They also say they believe federal officials are looking at prisons in Colorado and Montana; and in August, federal officials toured a maximum-security state prison in Michigan that was closed this fall because of budget cuts.

The prospect of housing terrorism suspects in Thomson has reopened a battle over the prison that began years ago.

In the 1990s, residents were divided over whether a state prison should be put here in the first place. Some said it would disrupt the quiet village once known for the watermelons grown on its farmland. Others said the jobs were desperately needed, particularly given the closings of several industrial plants, even before the national recession, and of so many businesses — two grocery stores, the five-and-dime, a barber, a pool hall — that old-timers fondly recall.

“Like most rural places, people just went away,” said Lee Schmidt, 92, who described the Guantánamo prison proposal as “lousy.”

The original prison debate was intense, sometimes personal, residents say; Ms. Pauley, who was village president then and supported the idea, said some people boycotted the ice cream shop she owned at the time. Some business owners along Main Street still refuse to speak publicly about the prison, saying they fear losing business.

Much like what we saw in "Prisontown," building a prison in rural Illinois hasn't been all its cracked up to be:

Consequently, this new push towards housing Guantanamo inmates in Thomson is creating a community-wide debate on the long-term effects this move will have to the community. Beyond the logistics of transporting inmates, residents are asking really important questions about long-range growth:By 2001, the prison — beige, pristine, surrounded by electrified fence and able to hold at least 1,600 prisoners, maybe more — was built, at a cost to the state of some $120 million. But then it sat. No prisoners came. Year after year, local leaders here said, the state said it could not pay to operate the place. In 2006, about 200 minimum-security inmates were finally moved here, but that gave jobs to only about 70 people.

Over the years, too, there have been new hopes raised, then dashed. Not long ago, local leaders said, an older state prison was rumored to be closing, and there was talk that all the prisoners would come here. Some locals even trained to become guards. But the move never happened.

On both sides of the issue, there are questions. Some opponents of moving Guantánamo inmates to the prison here wondered aloud: How would they be transported safely? Might they target Chicago, for its tall buildings? Would they draw family members and friends to the area?

Supporters wondered: How many jobs will this really mean? How many businesses will move in to serve that many prison workers? How much will the federal authorities pay the state?

The Obama Administration hasn't made a final decision yet, but whatever the decision, it looks like it will be bittersweet for the 600 residents of Thomson. As questioned above, perhaps housing these Guantanamo inmates will negatively impact long-term growth in the area. And yet, if they lost the opportunity to a rival prison community, like Hardin, Montana, the residents of Thomson may feel like they lost a serious boon in the midst of terrible economic times.

2 comments:

I think it says something about our current legal and socio-economic structure that towns are yearning for the right to house our prisoners. I know I have said this before on this blog but the fact that we have privatized many aspects of governmental services is something we should be more worried about. It really is the true legacy of Reagan. I truly believe that the "market" can be a cure for certain things but to assume that it can be a panacea is naive at best.

Aside from the tough economic decision this town is going to have to make, this post reminded me of the effects on the American psyche of putting prisons in rural places. I understand that prisons get built in rural places because urban areas lack the large tracts of land that they require. However, putting prisons in places like Thomson, IL, population 600, allows the rest of the population to forget the extent to which we detain people in this country. On a recent drive down Highway 99 in California, I lost count of how many small towns along the highway are also home to prisons. Even being somewhat aware of how many people are incarcerated in California, I still found myself shocked at the number of prisons. Perhaps we should build a maximum security prison right smack-dab in the middle of Chicago, so that as people walk to school and work each day, those who still have their liberty can be reminded of how many people don't.

Post a Comment